What are footnotes for? by Aurélien Bellanger

What are footnotes for?

by Aurélien Bellanger (translation mine, original here)

For a long while, the most important of my books was the big Folio edition of the Pre-Socratic philosophers. And I don’t even know if I ever really read it, but I absolutely had to possess it: these fragments had traveled through time, and they could be mine for less than 100 francs.

Philosophizing fragment by fragment

Anyway, it wasn’t so much possessing them as participating in their conservation. Anaximander, Empedocles, Parmenides, and Heraclitus had covered two and a half millennia, and I had something like a duty to them.

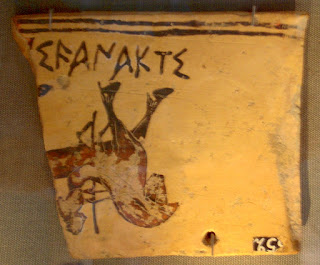

Even more so in that I had then only an imperfect mastery of the notion of fragments. I really thought that they were pieces of pottery that had gone through time, physically, like those little terra cotta boats that you find sometimes in the funerary furnishings of a profaned tomb.

I hadn’t thought that they could be in the state of literary fragments, more or less exact, that had survived. It was because Cicero returned to an argument with Democritus that Democritus has survived.

And this posits a real philosophical problem: what is more solid, a bit of ceramic or a rational argument?

There is fragment and fragment, even if one can imagine somewhat Borgesian situations where the physical object could be confused with the intellectual object, like some fragment from the hypothetical universe of Tlön, which has supposedly split into two smaller fragments, only to appear at once both in an encyclopedia and a jewelry box.

Let us consider for example Achilles’ arrow, which passed from the literary world to the philosophical, thanks to Zeno’s paradoxes, that we have since seen dissolve, with the invention of infinitesimal math, before the notion of the quantum came to give it a certain metallic hardness.

We also know Heidegger’s remark on the atomic bomb exploding first in the cogito of Descartes: the incarnation of philosophical arguments is a question more serious than it seems.

We can word the question another way; is the archeologist’s crucible more or less certain than the philosopher’s?

In their way, footnotes are a kind of response

Other philosophies than one's own

They are what the book doesn’t hold on to really but keeps anyway. Arsenic in the hair of thought. There we find the future philosophical fragment of tomorrow in its native state: what did not succeed in crystallizing in the page but that said page did not succeed in dissolving either. A contrary argument that we must mention. Something on the order of remorse, as well. For if one has not oneself succeeded in reducing to nothing the thing left in a footnote, one needs a certain sense of fair-play to mention it anyway.

The footnote is in that sense somewhat messianic: it is a step forward left to the future. This argument, that for my part I neglect, that I only mention in passing, I sense that it will survive me. This cliff I have climbed in taking an original footpath and perhaps with my bare hands. But I did indeed see it, to my right and my left, these old and empty clasps that the wind clattered against the cliff.

Would footnotes be the ghosts of former ascents? Or, put another way, relics. I evoked the question of the incarnation of philosophical arguments, the question of the fragment. I must also posit – by way of these abandoned grips, but left to the appreciation of other climbers – the question of the mind. To turn to footnotes is to grant, at the heart of an individual adventure, the most individual of all, perhaps, the writing of a book, a place to other minds. Unless the mind itself, or Mind, with a capital, should be only that: this thing that across time grips onto, hangs from, the footnotes

.jpg)

Comments

Post a Comment